Venomous Animals

Marine animals have various ways of incapacitating and killing their prey (assuming they are not

vegetarian!). Many, such as sharks, rely on speed of attack. But some marine animals are

equipped with highly toxic venom that can stun or kill their prey. As visitors to the tropical

coral reef environment, snorkelers and divers should know what creatures to be wary of. And

while it's never a good idea to pick up or touch anything on or swimming near the coral reef, it's

good to know what can potentially harm you or, in some cases, seriously injure you.

A note on the difference between "poisonous" and "venomous." It all has to

do with the method of delivery of the stuff that can hurt you. A "poisonous animal" is one

that has something on its skin that hurts you if you touch it, or has a toxin in its body that can

hurt you if you eat the animal. To be scientifically accurate, the creatures listed below are

all venomous, because they deliver their venom by stinging, slashing with spines, biting, or

harpooning their prey.

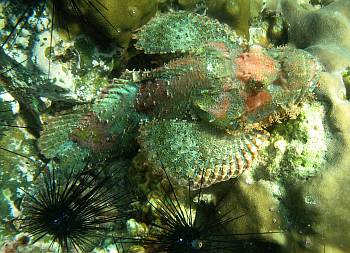

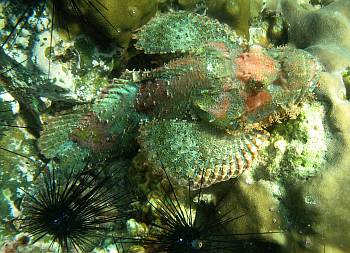

The most deadly of all venomous fish: Stonefish

| Stonefish belong to the same family as Scorpionfish and Lionfish, all of which have

toxins in their spines. Stonefish are found in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and the

Red Sea. While snorkeling in the rich coral reefs of the Butangs, in southern Thailand, our friend

Peter started prodding at what he thought was the edge of a seashell in the sand. To his

shock, it revealed itself to be not a shell, but the side of a Reef Stonefish

Synanceia verrucosa. He backed off immediately, shocked that he could have

unwittingly touched this fish, whose venom is the strongest of all fish poisons.

People die each year from accidently stepping on this fish that is either

partially buried in sand or nestled among rocks in shallow water where it looks like a rock,

or a big shell! Weird, ugly and deadly, the Stonefish has many warts, skin flaps, and

wide-set eyes, and as it curls up, it looks like a big glob of algae covered rock. Can you

see the tail? The eyes? The upturned mouth? The pectoral fin? The

Stonefish won't attack you, but if you bump into it, or touch it, the poison in the hollow spines

of its fins is very nasty stuff. (Photo: Sue Hacking. Butang Islands, Thailand) |

|

Lionfish and Scorpionfish also have venomous spines!

Lionfish are some of the most graceful and beautiful of all reef fishes. But their

pectoral and dorsal spines contain strong venom. A diver brushing up against a lionfish is

likely to suffer severe pain. Lionfish do not generally attack their prey, but instead they

rely on stealth, allowing their prey to come close enough to them to be stunned. For

snorkelers and divers, this means that lionfish tend to just hang out under ledges, beside dock

pilings, or under coral overhangs. To see them you often have to dive down and look up.

But don't approach too closely, as there might be more than one, or the fish may move suddenly,

brushing against you.

| This Clearfin Lionfish Pterois radiata was shot by

Chris on a night snorkel inside the reef in Raiatea, French Polynesia. It was hovering

just over a large coral bommie. It is distinguished from other lionfish

by the horizontal white band on the base of the tail. Like all lionfish, the

long, feather‑like pectoral and dorsal spines contain venom produced by

glands embedded in the spines. These fish hover near the bottom in wait

for crustaceans and small fish upon which they prey. They are solitary and inhabit

crevices during the day at 3‑15 m. (Society Islands, Fr. Polynesia) |

|

|

The Spotfin Lionfish Pterois antennata inhabits most coral reef

habitats, but deeper than the clearfin (above). This one was photographed

by Chris in daytime under a coral ledge in about 30' (10 m) on one of the wreck

dives in Tahiti. The spotfins are distinguished from other lionfish by

their translucent fan‑like pectoral fins with a few large spots (visible in

the photo like a web between the white spines). This is a fish to admire

from afar, given its very toxic spines. (Fr. Polynesia) |

|

The Common Lionfish Pterois volitans

(left and right) is probably the most common lionfish that we see. They

were abundant in Tonga and eastern Indonesia, floating above coral heads or on the sand.

They're almost identical to the Indian Lionfish, distinguishable by

range, and the Longspine Lionfish, distinguishable only with a

side‑by‑side comparison of dorsal height. (Photo left: Vanua Levu,

Fiji. Photo right: Vava'u, Tonga, by Jon Hacking.) |

|

| While snorkeling on a luxuriant coral reef on the northern coast of

Flores, Indonesia, we came upon several of these beautiful

Zebra Lionfish Dendrochirus zebra with their white fan‑like

pectoral fins displaying radiating brown lines. They are widely

distributed in the Indo‑Pacific but we have not encountered them very

often. Like other lionfish they like to hover just beside coral

structures awaiting their prey. The Zebra Lionfish feed at night, but

were out on the reefs at midday. Snorkeling, we had to be very careful

to look at where we were free diving so as not to swim into them. (Dondo,

Flores, Indonesia) Photo by Amanda Hacking |

|

Scorpionfish are related to lionfish, but they can hardly be considered graceful (they

tend to shuffle along the sea floor or coral walls) and we wouldn't rate them as beautiful.

Weird and interesting, yes, but not beautiful. They also have poison in their spines, but

instead of long willowy fins like the lionfish, they have short, sharp spines on their backs.

They can be very well camouflaged amongst the coral.

|

The Tassled Scorpionfish Scorpaenopsis oxycephala (left and

right) is probably the most common scorpionfish in the western Indo‑Pacific. We have

seen them in Indonesia, Thailand and

the Maldives. This is the largest scorpionfish attaining lengths up to 14 inches (36 cm) and

is named for the many skin tassels on its lower head. Scorpionfish are capable of

changing color to match their background. Venom is produced in glands on each side of the

hollow spines in the fins. A sting by a scorpionfish can be anything from mildly

painful to very painful and requiring medical attention. Quick first aid involves

soaking the affected area in hot water. (Photo left: Butangs, Thailand.

Photo right: Gan, Maldives) |

|

The well-camouflaged specimen face‑down on a wall of

coral (right) is probably a Papuan Scorpionfish Scorpaenopsis papuensis which

is smaller than the Tassled Scorpionfish. Appearance‑wise the 2 species are very

similar, both highly variable in color. One difference between the two has to do with

the size and number of scales along the lateral line (the Papuan having larger scales, and

fewer of them) but that's really hard to see in a photo. The Papuan Scorpionfish is found

in the western and central Pacific Ocean from Indonesia and Papua New Guinea east to

French Polynesia and north to Japan. (Photo right: Raja Ampat, Indonesia, by Jenna Miller)

The well-camouflaged specimen face‑down on a wall of

coral (right) is probably a Papuan Scorpionfish Scorpaenopsis papuensis which

is smaller than the Tassled Scorpionfish. Appearance‑wise the 2 species are very

similar, both highly variable in color. One difference between the two has to do with

the size and number of scales along the lateral line (the Papuan having larger scales, and

fewer of them) but that's really hard to see in a photo. The Papuan Scorpionfish is found

in the western and central Pacific Ocean from Indonesia and Papua New Guinea east to

French Polynesia and north to Japan. (Photo right: Raja Ampat, Indonesia, by Jenna Miller)

The Leaf Scorpionfish Taenianotus triacanthus (left) may be small,

but it can still inflict a painful wound if you brush against its spines. This fish was seen

on a wreck dive in the Maldives, at about 90' (30m). Leaf Scorpionfish grow to only

4 inches (10 cm) and can range in color from this reddish brown to white, yellow or pink.

Note the lower pectoral fin that is elongated into a sort of "foot" which the fish uses to

"walk" on the reef. (Photo: Gan, Maldives) |

Venomous Sea Snakes

Sea snakes are all venomous and they can produce 10‑15 milligrams of poison, but it

takes only 1.5 milligrams to kill an adult human! Luckily, they are generally not very

aggressive, but it pays to be cautious. Sea kraits (a family of sea snakes that give live

birth on land) are unable to strike while out of the water. But you still don't want to step

on one!

One of the more common animals on Tongan, Fijian and New Caledonian reefs is

the sinuous, curious, deadly Banded Sea Krait Laticauda colubrina.

Luckily the mouths of these animals are so tiny, and the fangs so far back, that it is very

difficult for them to bite anything as large as a part of a human! Banded sea kraits

are very docile when in the water, and while some diver guides handle these snakes, it is

never a good idea to do so. It is said that the one part of a human they can bite is

the fold of skin between the thumb and index finger. It is easy (and relatively safe)

to hover above a sea krait to watch as it pokes into crevices and under coral to find its food.

One of the more common animals on Tongan, Fijian and New Caledonian reefs is

the sinuous, curious, deadly Banded Sea Krait Laticauda colubrina.

Luckily the mouths of these animals are so tiny, and the fangs so far back, that it is very

difficult for them to bite anything as large as a part of a human! Banded sea kraits

are very docile when in the water, and while some diver guides handle these snakes, it is

never a good idea to do so. It is said that the one part of a human they can bite is

the fold of skin between the thumb and index finger. It is easy (and relatively safe)

to hover above a sea krait to watch as it pokes into crevices and under coral to find its food.

One theory on why their venom is so very deadly is because in order to incapacitate their

prey, it must kill them immediately, otherwise the prey would easily swim away. Sea

kraits (unlike sea snakes) come ashore to lay their eggs and we saw hundreds of them on

beaches in New Caledonia.

The black bands on the Banded Sea Krait continue fully around the body. The tails

of all sea snakes are flattened to aid them in swimming. Note there is no dorsal fin,

(or any other fin!) on the sea snake. A very similar looking creature, the Saddled

Snake Eel (which is NOT venomous) has the same black bands, but sports a full length dorsal

fin along its back. (Both photos: Tonga) |

The world's most poisonous sea snake is the Beaked Sea Snake

Enhydrina schistosa. This snake looks a lot like the Banded Sea Krait.

The key trait to look for is whether the black bands are continuous all the way around the

body. The Beaked Sea Snake has dark bands that get narrower as they wrap towards the

belly, then disappear altogether, giving the snake a pale white belly (see photo, right),

while the Banded Sea Krait is ringed all the way around. Both snakes can attain lengths of about

3.5 ft (1.2 m). (Photos: Left, courtesy of Jenna Miller. Right, photo by Sue

Hacking, backing away hurriedly from an agitated snake! Both photos taken in Raja Ampat,

eastern Indonesia.)

The world's most poisonous sea snake is the Beaked Sea Snake

Enhydrina schistosa. This snake looks a lot like the Banded Sea Krait.

The key trait to look for is whether the black bands are continuous all the way around the

body. The Beaked Sea Snake has dark bands that get narrower as they wrap towards the

belly, then disappear altogether, giving the snake a pale white belly (see photo, right),

while the Banded Sea Krait is ringed all the way around. Both snakes can attain lengths of about

3.5 ft (1.2 m). (Photos: Left, courtesy of Jenna Miller. Right, photo by Sue

Hacking, backing away hurriedly from an agitated snake! Both photos taken in Raja Ampat,

eastern Indonesia.)

Sea snakes need to breathe, just like snakes on land. Not much is

known about how long they can stay submerged, but 10 minutes is not uncommon. Some

scientists speculate that they may be able to stay underwater much longer than that.

Another sea snake we have seen, but not photographed, is a yellow sea snake that seems to

inhabit much deeper water, and we've encountered it swimming near the surface, far from land. |

Nasty Starfish:

Beautiful to look at, but a menace to coral, the Crown‑of‑Thorns Starfish

Acanthaster planci has become a blight around the world, devouring the

very reef it lives on. It would be nice to eradicate it from the tropical seas, but

don't even think about picking one up! Jon went on a Crown of Thorns hunt one

day, and tried moving one of these starfish with a piece of dead coral. His thumb came

in contact with the point of a spine and he was injected with venom. The injury was

not only painful, but his thumb swelled, turned white, and part of it went numb for months.

Bad stuff. The only natural predator of the Crown of Thorns Starfish is the huge

Trumpet Triton and unfortunately, despite being listed as Endangered, the Triton shells are

still collected to be sold in shell shops and markets throughout the world, leaving people

to try and solve the problem of the reef-eating starfish.

Beautiful to look at, but a menace to coral, the Crown‑of‑Thorns Starfish

Acanthaster planci has become a blight around the world, devouring the

very reef it lives on. It would be nice to eradicate it from the tropical seas, but

don't even think about picking one up! Jon went on a Crown of Thorns hunt one

day, and tried moving one of these starfish with a piece of dead coral. His thumb came

in contact with the point of a spine and he was injected with venom. The injury was

not only painful, but his thumb swelled, turned white, and part of it went numb for months.

Bad stuff. The only natural predator of the Crown of Thorns Starfish is the huge

Trumpet Triton and unfortunately, despite being listed as Endangered, the Triton shells are

still collected to be sold in shell shops and markets throughout the world, leaving people

to try and solve the problem of the reef-eating starfish.

The Crown‑of‑Thorns Starfish has 10‑20 arms with long, sharp spines.

Their color can vary from pale blue and red with tan spines to brilliant dark blue with black

spines. They are big starfish, reaching over 15 inches (38 cm). Like other

starfish, they can re‑generate arms that are cut off, making them very difficult to kill.

(Photo left: Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Right: Thailand)

|

Deadly Shells:

Beach combing and shell collecting seem like innocuous enough pastimes,

but there are a few really venomous creatures to be aware of. Textile Cones

Conus textile (left) are small (3‑4 inches or 8‑10 cm) gastropods (sea snails)

that have a poison sac in their head. When prey is nearby, or when threatened, the animal

ejects the poison via a harpoon‑like stinger, which projects from the "mouth" or proboscis at

the narrow end of the animal's shell. The venom produced by the cone shell is deadly to

humans, and these shells should never be handled casually or placed in a collection pouch

next to your skin. Textile cones and their close relatives all have triangular patterns of

varying colors and sizes. Because the live animal can withdraw fully into the shell,

it is not always possible to determine if the animal in the shell is alive or not. Be safe.

Never pick up a textile cone! These shells can be encountered throughout the Pacific

and Indian Oceans in shallow water and washed up onto beaches. (Photo: Fiji)

Beach combing and shell collecting seem like innocuous enough pastimes,

but there are a few really venomous creatures to be aware of. Textile Cones

Conus textile (left) are small (3‑4 inches or 8‑10 cm) gastropods (sea snails)

that have a poison sac in their head. When prey is nearby, or when threatened, the animal

ejects the poison via a harpoon‑like stinger, which projects from the "mouth" or proboscis at

the narrow end of the animal's shell. The venom produced by the cone shell is deadly to

humans, and these shells should never be handled casually or placed in a collection pouch

next to your skin. Textile cones and their close relatives all have triangular patterns of

varying colors and sizes. Because the live animal can withdraw fully into the shell,

it is not always possible to determine if the animal in the shell is alive or not. Be safe.

Never pick up a textile cone! These shells can be encountered throughout the Pacific

and Indian Oceans in shallow water and washed up onto beaches. (Photo: Fiji)

Another deadly cone shell is the slightly larger Geography Cone Conus geographus

(right) which is about 5 inches (13 cm) long. It is a more rounded, fuller cone than

the textile with a wide aperture, and an indistinct set of wavy and blotchy patterns.

This animal can extend more easily from its shell than the Textile Cone can because of its

open structure. There is no safe "end" by which to pick up a living Geographus.

Learn these shells, and never touch them! The photo on the right is of a broken,

beach-worn and bleached Geographus. (Photo: Fiji) |

Stinging Corals

The painfully stinging Firecoral Millepora spp. can be found in both the

Caribbean and Indo-Pacific regions. It can be an encrusting, branching (as shown,

left), or a more plate‑like coral. There area more than 12 Firecoral species, all of

which belong to the same genus, Millepore. Firecorals have 2 types of polyps.

The larger polyps are for feeding and are surrounded by defensive polyps, which are smaller

and contain stinging cells which release a toxin. While you don't have to worry

about a coral "attacking" you, you do have to beware of brushing up against it, or holding

onto it. Vinegar, or, believe it or not, urine (with its uric acid) are both good

antidotes to the stings if applied soon after the encounter. Rubbing the area may

spread the nematocycts and cause more of them to break. Ouch! (photo: Indonesia)

The painfully stinging Firecoral Millepora spp. can be found in both the

Caribbean and Indo-Pacific regions. It can be an encrusting, branching (as shown,

left), or a more plate‑like coral. There area more than 12 Firecoral species, all of

which belong to the same genus, Millepore. Firecorals have 2 types of polyps.

The larger polyps are for feeding and are surrounded by defensive polyps, which are smaller

and contain stinging cells which release a toxin. While you don't have to worry

about a coral "attacking" you, you do have to beware of brushing up against it, or holding

onto it. Vinegar, or, believe it or not, urine (with its uric acid) are both good

antidotes to the stings if applied soon after the encounter. Rubbing the area may

spread the nematocycts and cause more of them to break. Ouch! (photo: Indonesia)

Other dangerous marine animals are the Stinging Hydroids (right) a form of soft

coral. These feather‑like colonies look more like plants than animals.

Most have a chitinous exoskeleton (the part that looks like the branches of the "plant") from which

extend the polyps with their singing cells. These cells are microscopic stinging structures

called nematocycts that can inflict serious pain when they break off against your skin. (Photo: Derawan, Indonesia) |

Up | Nudibranchs | Coral Reef | Venomous Animals | Angelfish | Butterflyfish | Damselfish | Puffers | Sharks & Rays | Snappers & Breams | Surgeon/Rabbit Fish | Triggerfish | Wrasse & Parrotfish | Other Reef Fish

Reef Animals | UW Photo How-to | Scuba Diving

Top Level:

Home |

Destinations |

Cruising Info |

Underwater |

Boat Guests |

Ocelot |

Sue |

Jon |

Amanda |

Chris |

Site Map |

Make a Comment

|

Lifetime

Commodores

of the

Seven Seas

Cruising

Association |

|

|

If our information is useful,

you can help by making a donation

|

Copyright © 2000‑ Contact:

Jon and Sue Hacking -- HackingFamily.com, svOcelot.com.

All rights reserved.